FL 3320, European Studies: Sample Student Papers

Sample # 1: 19th century Paris: The Spirit of an Era reflected in Photography

Nineteenth century Paris was a hub for creative individuals from all over the world. The tumultuous atmosphere of an era in which one invention inspired the next and people from diverse fields of interest vividly interacted with each other is well described in William R. Everdell’s essay "The First Moderns". In the chapter "The Century Begins in Paris", Everdell creates a lively picture of Paris where Loie Fuller asks Marie Curie about the use of radium for theatre lighting (Everdell, 149), Paula Becker is inspired by Cezanne’s paintings (Everdell, 145), and Gertrude Stein studies under William James (Everdell, 150). The official birth year of photography, 1839, was also marked by commotion. Experiments with photography had been conducted simultaneously in different countries, yet it was French painter and chemist Louis-Jacques-Mandes Daguerre who first presented his findings to the public, much to the dismay of his English competitor William Fox Talbot who had planned on publishing his results only a few days later. The various applications of photography, for instance, in art and science perfectly complemented the versatility of interests. In a way, its use illustrates the peoples’ mind-set and symbolizes the changes during a time in which new inventions were celebrated, yet letting go of the past often presented itself as a challenge.

This aspect is particularly apparent in portraiture. Since Daguerre ’s pictures were very detailed, photography soon largely replaced portrait painting. Some of the most compelling portrait photographs were taken in the nineteenth century. These pictures often reveal the individuals’ insecurities in front of the camera, as well as their pride to be photographed. It is striking how avidly French photographers, particularly Gaspar-Felix Tournachon, also known as Nadar, photographed celebrities. These photographs of individuals like Honore Daumier, Honore de Balzac, H. Eugene Delacroix, and Charles Baudelaire (Artcyclopedia) witness Nadar’s awareness of how momentous the period was in which he lived. It appears that he felt a need to document that these important individuals lived around the same time and met in Paris. The comprehensive image of nineteenth century Paris where great ideas seethed and remarkable individuals met is visually as well presented by Nadar’s photographs as by Everdell’s written summary.

Walter Benjamin describes in his essay "Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century" the "reactionary" attitude people often had in conjunction with an enthusiasm for the new. Benjamin refers to this attitude, for instance, when he writes about iron as a newly discovered building material, "The Empire saw in this technique an aid to a renewal of architecture in the ancient Greek manner" (Benjamin, 147). Photography combines just these aspects of sentimentality for the past and enthusiasm for the new. The new medium, technically so progressive had been designed to produce testimonials of the past. By taking pictures, the photographer preserves a moment in time and creates a visual proof that something or someone existed at the time the picture was taken. Thus, Nadar’s photographs constitute a rather sentimental retrospect onto the past. Furthermore, early photographs with their painted backgrounds and overall artificial set-up frequently resembled traditional portrait paintings. Photographers like Louis Jules Duboscq-Soleil turned still-lives, favorably the traditional memento mori, into a photographic depiction (Geschichte der Photographie, 46).

In 1851, the French government assigned five photographers to photograph historical buildings and monuments throughout France. Visual proof for the architecture’s decay was supposed to be collected on this Mission Heliographique in order to plan restoration. However, with misty backgrounds, visual pleasing proportions like the golden mean, and the prints’ fine silvery tonality, the final photographs appear like artistic, atmospheric images rather than neutral observations of architectural aspects. The photographers utilized their medium as a modern practical tool for observation, yet created (perhaps unintentionally?) imposing pictures of historical monuments. It may be said, that the artists’ pride in the traditional and the adaptation to the modern technology are apparent in their photographs. These pictures illustrate the medley of old and new, which was to be found everywhere in nineteenth century Paris and would later be attacked by the Futurists.

Artists who did not accept photography as an art form in itself also utilized the medium as a device facilitating the painting and drawing process. Landscape painting became less strenuous for painters, since they did not have to spend long periods of time in the countryside but were able to paint in their studios with photographs as their models. Furthermore, light logic, the different ways how light reflects from objects, could be closely studied from a photograph which was a great advantage over the ever-changing lighting situation outdoors (Early Reactions to Photography). The multipurpose application of photography demonstrates the flexibility of thought that persisted during this period. People did not just accept innovations for what they were, but appropriated them for purposes of their own interest. Fourier takes the principle of arcades and proposes to turn these structures into living accommodations (Walter Benjamin 148); similarly, many painters accepted photography not as a form of art in itself, but as a tool for their purposes.

Not only did photography facilitate the painting process but it forced the traditional arts to be re-defined. (Geschichte der Photographie). Romanticism was superseded by Realism in the mid-nineteenth century signifying that peoples’ interest in a transfigured world-view had shifted to attention of reality. On the one hand, by creating the perfect illusion of three-dimensionality on a two-dimensional surface, and by depicting great detail, photography certainly contributed to the idea of realism in painting; on the other hand, because of its ability to produce visual copies of reality, it made realism dispensable and sparked artists to bring about entirely new art movements concerned with abstraction, such as Cubism. Moreover, philosophers found interest in contemplating the relationship between photography and reality. Some people argued that every photograph is subjective, since the photographer chooses at least the perspective and the angle from which the picture is, taken and thus manipulates the picture. Others held the view that photographs are by nature absolute true representations of reality (Geschichte der Photographie). The concern with the definition of reality is a logical consequence in regard to a medium which presents so dramatically naturalistic depictions; more importantly, this concern is also a logical consequence of the events taking place in the nineteenth century. People experienced reality through political turmoil (Everdell, 146), drastic inventions such as the city lighting, and confrontation with radical art movements. Contrary to this, a rather surreal feeling was conveyed by mind-boggling changes such as the invention of movies; people were tempted into increasingly overwhelming commercial settings (Benjamin 146) as well as establishments like the Moulin Rouge that had been created to carry its visitors into an artificial world. Reflections on the meaning of "reality" were inevitable; photography was one of the essential factors to begin this contemplation.

The camera’s property of automatism was intriguing to many people, especially those interested in technology. Initially, people considered the photographer to be detached from the photographic process. Light was believed to be the decisive factor in "pai nting" the images of objects onto a flat surface, whereas the photo grapher was seen as the one to merely press a button (Geschichte der Photographie 33ff.). This attitude shows the glorification of technology which would become so characteristic of the Futurists who perceived their environment, including life-less objects as animated.

The application of photography furthered and refined scientific research. Not only did researchers use photographs for cataloguing their collections, but images like Eadweard J. Muybridge’s sequential photographs of movement demonstrated operations formerly invisible to the naked eye. In the 1840’s, E. Thiesson returned from South Africa to Paris, bringing with him photographs of the native peoples for ethnographic studies (Geschichte der Photographie, p.53). Peoples’ curiosity about the function of things and distinguishing features of humans as well as their urge to make sense of the fast-paced world was very much accommodated by photography.

This medium, first and foremost Muybridge’s photographs also, inspired brothers Auguste and Louis Lumiere to invent the film in 1895. Thereby, photography did exactly what happened all over Paris during the nineteenth century: It instigated new ideas. Futurists alike were influenced by photography. Long exposures captured movement on a two-dimensional picture plane. The idea of depicting implied movement in a still picture led to creations like Marcel Duchamp’s painting "Nude Descending a Staircase" (Artcyclopedia).

Worth mentioning is that photography significantly influenced commercialism. Fashion photographs first appeared in Paris toward the end of the nineteenth century and triggered the idea of fashion magazines. As Benjamin mentions in his essay, "…advertising [is] a word that is also coined at this time" (Walter Benjamin, 152). Photography was undoubtedly a significant factor in encouraging people to immerse themselves into the world of consumerism; it played an important role in shaping Paris, in transforming it into a fashion metropolis and in attracting the masses. With all its peculiarities and its contributions to different fields of interest, photography was (and is) a medium befitting the eventful nineteenth century. The controversial aspects of this invention in conjunction with its progressive quality almost let photography appear as a symbol for nineteenth century Paris.

Works Cited

Artcyclopedia. Ed. Malyon, John. 2006. <http://www.artcyclopedia.com>. March 25th, 2006.

Benjamin, Walter. Reflections�" Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century. <http://ereserve.weber.edu/eres/default.aspx>

Brown University. Early Reactions to Photography. Ed. Publishing Service. 2006.

<http://www.brown.edu/Courses/CG11/Group008/EarlyReactionstoPhotography.htm>

Everdell, William R. The First Moderns. Profiles in the Origins of 20th-century Thought. Chicago: The U of Chicago P, 1997.

The George Eastman House Collection. Geschichte der Photographie. (1st ed.). Koeln: Taschen, 2000.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2006. < http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/heli/hd_heli.htm>

Sample # 2: A Cultural Esperanto: Dada, or, the Anti-Art

Question: How many Dadaists does it take to change a light bulb?

Answer: A fish

The Dada art movement of 1916 to roughly 1920 began in confusion and ended in chaos. Dadaism was characterized by a general need to revolt against established art forms and to find something which stood in the face of traditional cultural values. Dada was not formed so much by a specific group of artists as it was created out of the necessity to satisfy the desire to react to the horrifying events of World War One (Hopkins 2). While many cities and individuals are often cited as precursors to Dada, the movement’s beginnings are generally attributed to Zurich, Switzerland, and to the members of the Cabaret Voltaire, most notably Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara. An exploration of the Dada movement and its history, as well as a look some notable examples of Dada art and at potential reasons behind Dada’s downfall, will begin to clarify this confusing but important theme in European history.

Zurich served as the scene for the birth of Dada simply because it was the one of the only havens in Europe for dissenters and conscientious objectors to the war which, by 1916, had consumed the entire Continent and much of the world. The artists who flocked to Zurich were appalled at the atrocities of the war and of a culture that could perpetrate such destructive acts. In order to voice their contempt, they needed a medium of expression, however, and the extant models of Expressionism and other “bourgeois” practices were unacceptable to this new generation of artists who strove to reinvent art in order to interpret their world. In order to do this, everything would have to be changed about art and reinterpreted through the new light of Dada. Traditional forms of art were thrown out completely and literary genres altered or else entirely reinvented. Dada artists began to look for alternative methods of creating art, such as collages, photomontage, ready-made (or found) art, automatic-writing, phonetic poetry and anything else a Dadaist could utilize in his or her craft.

Perhaps one of the most iconic examples of Dadaist art comes from Marcel Duchamp, a French artist who contributed heavily to both Dadaism and, later, Surrealism. In his famous Fountain, shown below, Duchamp presents a urinal, a ready made form of art, as a fountain. In doing this Duchamp inverts the meaning and function of a common item with the intent of creating discord in his audience.

Duchamp’s Fountain was ultimately rejected as a submission to the Armory Show in New York (Dachy 70). However, through the ensuing controversy about this piece, Duchamp ultimately realized one of the primary Dadaist tenants of rejecting conformity. About his work Duchamp comments, “My Fountainwas not a negation; I just tried to create a new idea for an object that everyone thought they could identify. Everything can be something else; that is what I wanted to show” (Dachy 73). Duchamp’s art initially caused controversy but started vital debate about the validity of traditional art forms, and this created interest in the movement.

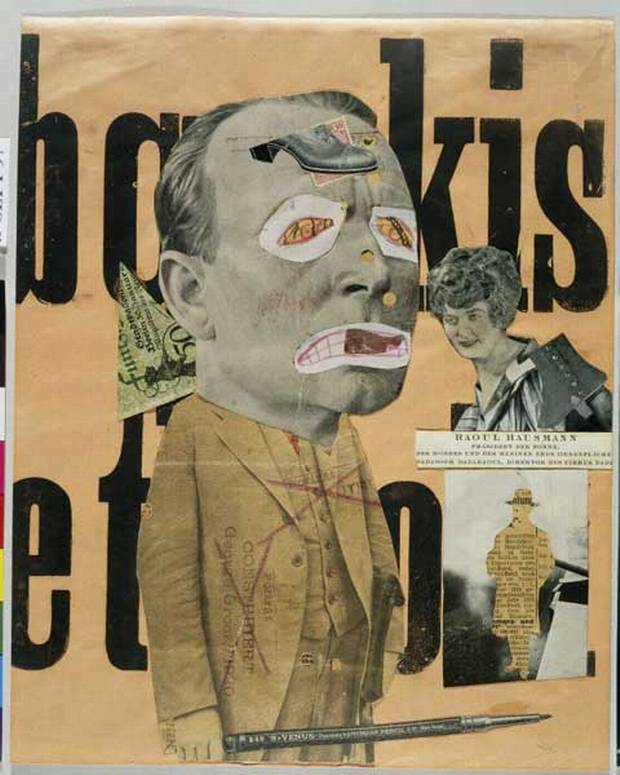

Another prominent form of Dadaist expression comes through the form of photomontage, a collage-like series of cut out photos and other articles superimposed on each other in an attempt to create new meaning from already existent messages. The work of German artist Raoul Hausmann is often cited as a strong example of this medium, and about his photomontage Der Kunstkritiker, or The Artist (shown right), Hausmann praises this art form for “the new material’s ability to irritate, and in so doing lead to more fresh types of content” (Dachy 36).

Through Der Kunstkritiker, Hausmann uses jarring images to shock the viewer into considering potentially new artistic applications and cultural practices. About Hausmann’s work, Dachy writes that Dadaists used photos “to create a new entity that drew from the chaos of war and the revolution and intentionally new optical image” (Dachy 36). These new optical images, much like other Dadaists’ ready made art, were created with the intention of abrasively confronting the audience with the challenge of reforming traditional thought patterns.

The negative view of pre-established cultural and artistic manifestations was reflected not only through Dada art, but through the lives of the movement’s artists as well. About this theme Hopkins writes, “In Dada a basic distrust for the narrowness of art frequently translated into open antagonism towards its values and institutions” (4). This theme of open antagonism is central to Dada; the creators of this art often set out to deliberately provoke and antagonize the audience in their continued rebellion against what they ultimately viewed as a corrupt and unrespectable society.

The Dadaists viewed their world as absurd and this is a theme that is reflected throughout their work and actions. The very name “Dada” is nonsensical, and while the exact origin of the name is unclear, it is likely that it either means “yeah, yeah” in Romanian, “farewell, goodbye” in German, or “hobby horse” in French; the idea behind this name is that, since the art form was a reflection of the absurd, then its name should be nonsensical as well. These vagaries extend even farther when the observer learns that Dada embraced any medium or material as long as it expressed the absurd. This means that Dada exhibitions would regularly range in content from poetry readings to plays to political demonstrations and more. Tzara gives a classically Dadaist effort when, explaining the origin of the movement. He says, “A word was born, no one knows how, DADA…the most intense affirmation salvation army freedom oath mass combat speed prayer tranquility guerilla private negation and chocolate of the desperate” (Dachy 16). Indeed.

Once the Dada movement was firmly established at the Cabaret Voltaire, it began its campaign across Europe and, later, into America. In 1916 Ball and Tzara began publishing Dadaa journal showcasing collections of this new art form. Shows at the Caberetoften introduced new art forms, such as Ball’s “Sound Poems,” in which he would write using invented phonetic expressions. A good example of this new form of artistic expression can be seen in Ball’s famous poem “Karawane,” when he writes:

Gadji beri bimba

Landridi lauli lonni cadori

Gldjama bim beri

Glassala / glandridi (Dachy 27).

Ball later moved on from the scene, and Tzara took over the Cabaret. In 1918 he published a manifesto which told the world that “I am destroying the drawers of the brain and of social organization; the aim is to demoralize the whole world…to reestablish the fertile wheel of a universal circus in the real powers and the imagination of every individual” (Dachy 26). This would be the beginning of Tzara’s aggressive and confrontational campaign for the establishment of a worldwide Dadaist movement.

In the same year the movement spread to Germany where it took on a more decisive political tone against the German government who, in the eyes of the Dadaists, were solely responsible for leading the country into four years of death, destruction and economic depression. The German Dadaists, based primarily in Cologne infused their demonstrations with posters bearing slogans such as, “Die Kunst is tot” (art is dead) and “Dada steht auf Seiten des revolutionaren Proletariats! (Dada is on the side of the revolutionary proletariat!). One major form of Dadaist expression in Germany came through the use of “Urban Detritus,” basically garbage, as a material for creating art. For the German Dadaist, the use of garbage in creating art likely reflected the artist’s disdain for the country’s government and culture.

In 1920 Dada made another leap, this time into Paris where Tzara, together with the artist Breton coordinated “the Dada Festival in the Salle Gaveau [and] gave the movement a great deal of publicity” (Dachy 82). By this time the movement had attracted the attention of the world and Dadaism had even moved across the Atlantic Ocean into some of the small artistic circles of the New York City elite. However, while the level of publicity in Paris far exceeded that of Zurich and Cologne, the atmosphere was decidedly more apolitical and nationalist in its tone. French artists like Breton were more reluctant to take confrontational stances against the government than their Swiss and German predecessors (Gale 180). This atmosphere and circle of artists would ultimately asphyxiate the movement, and it was in Paris that Dadaism officially started to lose momentum.

After some particularly confrontational and controversial showings in Paris, a rift grew between Tzara and Breton and the two artists began to display their art at separate exhibitions. A series of confrontations between the two artists ended when Breton and some of his associates stormed into a showing of Tzara’s play The Gas Houseand instigated a fight with Tzara’s company, breaking the arm of one actor and injuring others. Once this final act was completed, the death of Dada was ensured. The movement continued for awhile intermittently but without the fervor of its younger years. Dachy writes that “Although the end of Dada did not take place officially until the summer of 1923, for Tzara something was already ending earlier, in any case by the fall of 1922, when at his ‘Lecture on Dada’…he proclaimed the death of Dada and reaffirmed his hostility to modernism” (Dachy 89). The extant Dadaists broke up and the Cabaret Voltaireeventually folded. Many artists quit producing art and those who continued to produce generally melded into the ensuing Surrealist movement which shared some of the same ideals as Dadaism.

The end of Dada is actually telling of the reasons for its beginning and continued existence throughout its prime. While strongest in Zurich and Cologne, Dada thrived on conflict and depended on cultural upheaval. Dada in Zurich depended as much on disgust for the war as Dada in Cologne needed being on the losing side of a world war to fuel its angst. However, when the movement reached Paris it died because the atmosphere in France at the time was not conducive to the combative nature of Dada. The country had recently won the war and had been taken over by a new nationalistic, conservative government (Gale 189) that created an unhealthy atmosphere for dissidence. From this we can conclude that Dada was born in conflict and depended on chaos to survive. Without strife, Dadaistic expression was meaningless.

WORKS CITED

Dachy, Mark. Dada: The Revolt of Art. New York: Abrams, 2006.

Duchamp, Marcel. Fountain. 1917. Cégep du Vieux Montréal. Montrél, Canada. 22 Mar. 2007. <http://www.cvm.qc.ca/mboudreault/Images%20Jpeg/Marcel%20Duchamp.jpg>

Gale, Matthew. Dada & Surrealism. London: Phaidon Press Ltd., 1997.

Hausmann, Raoul. Der Kunstkritiker. 1923. National Gallery of Art. Washington D.C., USA. 22 Mar. 2007. <http://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2006/dada/images/artwork/202-078-cities.jpg>

Hopkins, David. Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.