American West -- Dumping Ground

We will consider two issues--the Internment of Japanese Americans in World War II and the post-war development of nuclear weapons and energy.

Japanese Relocation Camps

Fearing more Japanese attacks on their cities, homes, and businesses, government leaders in California, Oregon, and Washington, insisted that the Japanese residents be removed and placed in isolation farther inland. Facing the uncertainty of war and mounting pressure from the people, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which resulted in the forcible internment of people of Japanese ancestry.

It was without serious incident that one of the largest migrations in history took place in early spring of 1942. Under military supervision, the U.S. Government evacuated more than 110,000 people of Japanese descent and placed them into 10 wartime enclaves. More than two thirds of those interned under the executive order were U.S. citizens, and none had ever demonstrated any disloyalty.

Readings: explore one of the following:

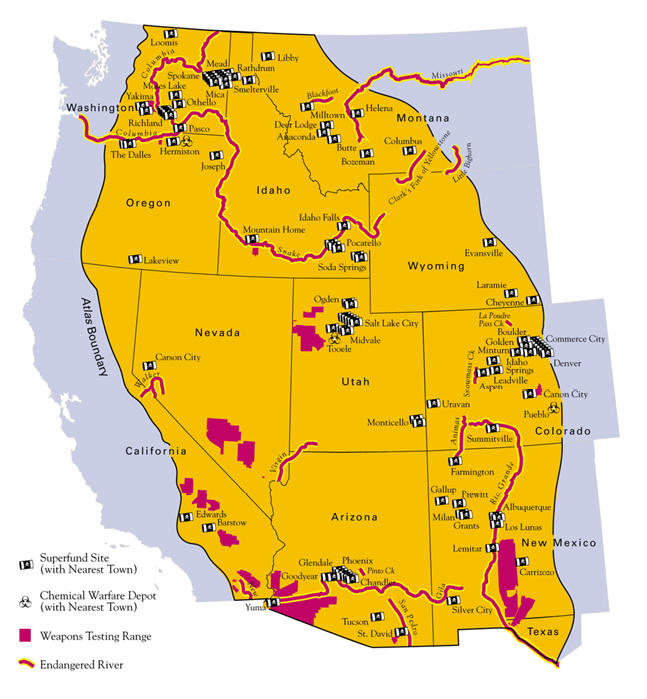

Toxic Waste Sites in the West

(Source: http://www.colorado.edu/AmStudies/lewis/west/ddream.htm)

Acting on an enduring perception of the American West as an

"empty" place, the U.S. government located a disproportionate number of nuclear

facilities-particularly the ones most likely to spread pollution-in western

states. The Manhattan Project manufactured plutonium at Hanford, Washington;

designed and assembled bombs at Los Alamos, New Mexico; and detonated the

world's first atomic bomb at Alamagordo, New Mexico, on June 16, 1945.

In the years that followed the war, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission selected

additional western sites for its work. Many westerners initially welcomed the

atom. Like federal officials, they, too, regarded their region as "empty," or

underdeveloped. Facilities to make, test, and base atomic weapons, sites to

store nuclear waste, and even nuclear power plants were regarded as assets. By

the 1960s and 1970s, however, regional attitudes began to change. At a variety

of locales, ranging from Eskimo Alaska to Mormon Utah, westerners devoted

themselves to resisting the atom and its effects on their environments and

communities. Just as the atomic age had dawned in the American West, so its

artificial sun began to set there. (See: The Atomic West,

edited by Bruce Hevly and John M. Findlay, 1998.)

The American West has long been seen, at least by the powers in Washington, as a dusty outback that is just right for testing nuclear weapons and dumping toxic wastes of various kinds (``these dry, arid regions are perceived and discursively interpreted as marginal within the dominant Euroamerican perspective''). That outback is the domain of Indians, who view it differently, as sacred geography; thus, the government's misuse of Western lands is a form of environmental racism. (See: The Tainted Desert: Environmental and Social Ruin in the American West by Valerie Kuletz, 1998)

Readings:

Paper # 8: Comment on the legacy for the West of one of the above topics.