History 4120 20th Century West Spring 2004 MacKay

Week 1 The West--sources

projects: explore the following Internet sites and report your findings orally and in your journal:

WestWeb is a topically-organized website about the study of the American West created and maintained by a born-and-bred Westerner, Catherine Lavender, of the Department of History, College of Staten Island, The City University of New York: http://www.library.csi.cuny.edu/westweb/

From Washington State University is a web site on the Multicultural American West: http://www.wsu.edu:8080/~amerstu/mw/

From Wikipedia, a discussion of the region: http://en2.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_West

readings: maps of the New West

Internet sites on the creators of the West myth

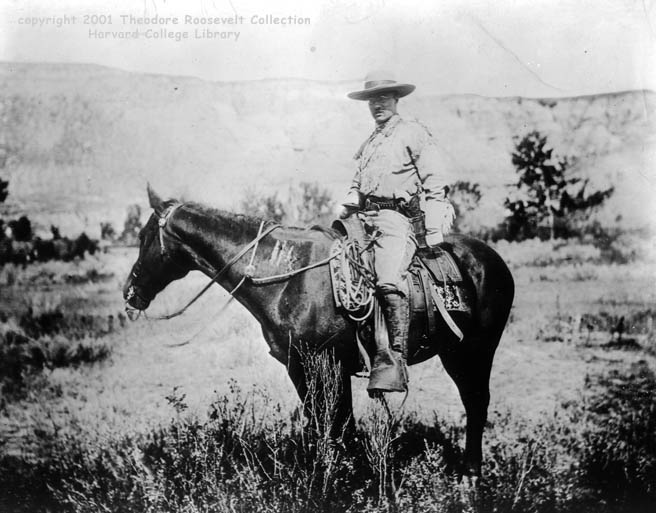

The West myth operates as a "functional myth," a form that allows societies to "act out the conflicts symbolically" when ideals and reality clash. The spread of urban-industrial landscapes over agrarian space (geographic and cultural) in the post-Civil War years threatened America's core values: "individualism, self-reliance, democratic integrity." In Britain, industrialism affected a revival of the Arthurian myth. The collision of industrialism with America's Republican, agrarian value system and the belief in the "tragedy" of a "finished" West, resulted in a unique American response and the creation of the West myth. The historical timing also provided the focus on the cattle era and the Northwest cowboy of Wyoming, Montana, and Dakota (not Texas).Buffalo Bill Cody, Theodore Roosevelt, Frederic Remington, and Owen Wister all played primary roles in the "deliberate" creation of America's West myth and its central hero, an "entirely" manufactured cowboy. Roosevelt's Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail (New York, 1888) popularized an emergent "courageous and heroic" cowboy not the historic wage-earning man who prepared cattle for the meat industry. The painter Remington dramatized moments of cowboys, Natives, horses and cattle in scenes of "acute danger." Owen Wister, author of The Virginian (New York, 1902) and an 1895 Harper’s Weekly series, "The Evolution of a Cowboy," created the style of the cowboy-of-image (slow, silent, spare, irresistible, and invulnerable). These eastern men wove "bits of history," personal experience in the West, and desires to escape from the East, into a myth that encompassed their own transformed identities. Frederick Jackson Turner justified the myth intellectually. These prominent male mythmakers, however, merely reflected the larger culture and knew not what their predilections codified

Frederick Jackson Turner

In "The Frontier in American History," Frederick Jackson Turner, a past professor of American history at the University of Wisconsin and Harvard University, argues that American democracy and Americanism were made in the West. Although the boundaries of the West--also referred to as the frontier in this text--were constantly shifting further westward, Turner believes that this frontier always shared a similar set of values. He furthers this by saying that the values possessed in the West were many times in conflict with Eastern ideals. Frederick Jackson Turner illustrates how many of the conflicts between Eastern and Western ideals the West won, because it was the frontier always which was creating the new race of Americans. The West, Turner contends, created the type of many who is the American race, not a transatlantic European, but something entirely different from all other races. He argues that the fight for the frontier has been the distinctive feature of American history. In his words, "America's contribution to the history of the human spirit has been due to this nation's peculiar experience in extending its type of frontier into new regions; and in creating peaceful societies with new ideals..."; Turner notes that essays are a valuable source to read collectively, because they are commentaries in different periods on the central theme of the influence of the frontier in American history. The cultural landscape in this text, the frontier, has continually shifting boundaries with sets of distinctive ideals and Frederick Jackson Turner in this work describes both of these characteristics. [J. Bixler]

"The Significance of the Frontier in American History" http://www.library.wisc.edu/etext/WIReader/WER0750.html

Owen Wister

The Virginian: http://www.cowboypoetry.com/wister.htm

Frederick Remington

http://www.traverse.com/people/dot/remington.html

Frederick Remington Art Museum: http://www.fredericremington.org/

William "Buffalo Bill" Cody

http://www.americanwest.com/pages/buffbill.htm

Buffalo Bill Historical Center: http://www.bbhc.org/

Theodore Roosevelt

The Winning of the West: http://www.artsci.wustl.edu/~landc/html/roosevelt.html

In the preface of this book Professor McElroy says that The Winning of the Far West "was written at the instance of the publishers, to constitute a continuation of Colonel Roosevelt's Winning of the West." We have a right to expect then a continuation of Roosevelt's work, taking it up where he dropped the subject and doing for the Far West what Roosevelt did for the Mississippi Valley. Roosevelt grasped the fundamental conception of the winning of the west in his opening chapter on "The Spread of the English-speaking Peoples." To him the winning of the west was the story of the frontiersman crossing over the Appalachians, occupying the Ohio Valley, and rudely jostling the Indian and the Frenchman. Once established, he played no mean part in the Revolutionary War in the winning of a title to the lands as far as the Mississippi River. After the war, came a second great wave of migration which reached to the Mississippi and beyond, and to the north and the south, involving the Westerner in a struggle with the Indian and the Spaniard. The title finally secure and the lands being gradually occupied, Roosevelt then turns back to view the development of state and territorial institutions, ever bearing in mind the flow of population and the crowding of the Indian. Then follows the story of the settling of the frontier difficulties and the acquisition and exploration of Louisiana. Such in brief outline is Roosevelt's work, admirably conceived, and though at times inadequate, still the best single work that has been done on the period.

Perhaps the most self-conscious moralist of television's first western stars was Gene Autry, who in the early 1950s authored the Cowboy Code:

1. A cowboy

never takes unfair advantage, even of an enemy.

2. A cowboy never betrays a trust.

3. A cowboy always tells the truth.

4. A cowboy is kind to small children, to old folks, and to animals.

5. A cowboy is free from racial and religious prejudice.

6. A cowboy is always helpful, and when anyone's in trouble, he lends a

hand.

7. A cowboy is a good worker.

8. A cowboy is clean about his person, and in thoughts, word, and deed.

9. A cowboy respects womanhood, his parents, and the laws of his country.

10. A cowboy is a patriot.