History 2700 MacKay

Week 4 Colonial American Life; Subsistence economies

In the broadest sense the American colonial experience

was not unique in history. Following the discovery of the New World by

Columbus, the European nations—primarily Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands,

France, and England—set out to build colonial empires based on certain

assumptions: First, colonies would make them wealthy and powerful and give

them advantages over their neighbors. Second, the acquisition of colonies

would enable them to solve various social problems such as overpopulation

(relative to available land and food supplies), poverty and the crime that

was often related to chronic underemployment for much of the population.

Third, there existed a general sense that since the poorer classes knew that

they had little chance of improving their lives, which might tend to make

them rebellious, colonies could serve as a sort of escape valve for pent-up

frustrations. Whatever the motivations, most major European nations

vigorously pursued colonial policies.

By the time the first English colony in North America was established in

Jamestown in 1607, Spain and Portugal had colonized most of what we now call

Latin America, and French and Dutch settlements were being established in

the Caribbean area as well as in east Asia and elsewhere around the globe.

By the time of the American Revolution Great Britain possessed 31 colonies

around the world, including some—Canada and Florida for example—wrested from

colonial competitors such as France and Spain. Thus the American colonies in

1776 were but 13 small parts of vast colonial empires that had been growing

since the early 1500s.

The first thing to remember about the colonial experience is that it was

difficult. Imagine getting into a ship in which you and about 100 other

people, mostly strangers, have not much more space than exists in your

college classroom or perhaps a small house, carrying with you only as much

personal property as you can fit into a couple of suitcases You sit in that

ship for perhaps days or even weeks until suitable winds and tides take you

out to sea, and then you toss and rock for weeks or months, as food spoils,

water becomes foul, people get sick and often die, storms threaten (and

often take) life and limb of everybody on board. If you survive that ordeal

(and many did not) you finally arrive on a distant shore, disembark with

whatever provisions have not been ruined by salt water, and set out to make

yourself a life. Particularly in the earlier years of colonization, there

was not much there to greet you when you arrived.

The second point about the colonial experience has to do with the people

who came. Many came voluntarily, many came under duress of some kind. (We

will discuss the African experience, which brought thousands of slaves to

the New World, below.) Those who came voluntarily thought they could make a

better living. They dreamed of finding gold or silver, or of a life that

would reward them in ways that were impossible in their circumstances at

home. Some felt oppressed by political conditions—required obedience to king

or duke or other landlord—which they found intolerable. Some came for

religious freedom, to be able to practice their faith as they wished. Some

were moderately prosperous, and saw the New World as an opportunity for

investment which would allow them to move up a few notches on the economic

scale. Most had to have something to offer—a skill such as blacksmithing or

farm experience or the price of passage—so the poorest of the poor, who were

generally chronically unemployed and had no skills to speak of, tended not

to be among the colonists who came voluntarily. Naturally the very

wealthy—the landowners, the nobility, the prosperous merchants—did not come

because they had too much to lose and the risks were too great.

Those who came involuntarily, aside from the African slaves who were

brought to the Americas, included prisoners, debtors, young people who were

sold by their parents or people who, in effect, sold themselves into

indentured servitude. That experience—indentured servitude—was as varied as

the people who practiced it, either as owners of their “servants’” time for

a stipulated period or those whose time belonged to somebody else. Some

indentured servants—say a young married couple with skills to offer, the

husband perhaps as a carpenter and the wife a seamstress—might make a decent

bargain for themselves, and given a decent person for whom to work, come out

of the experience with a little money, or some land or perhaps a set of

tools which they could use to start their own lives. Periods of service

varied from two or three to seven years or more, depending on all kinds of

variables. Quite often, possibly in the majority of cases, indentured

servants found their lives less than ideal. Laws tended to protect the

masters, punishments for laziness or attempting to run away were frequently

harsh, and both men and women were subject to various kinds of abuse. For

most, the period of indenture was most likely seen as a trial to be endured

as best one could, with a reasonable hope of some sort of a stake in the

future when the service was complete. In some cases, very warm relationships

no doubt developed, and indentured servants could find themselves more or

less adopted into the family, perhaps through marriage or extended

friendships. Whatever the odds may have been at any given time for any

person or group, indentured service was a gamble. When the contracts were

signed in Europe, those offering themselves for service had little knowledge

or control over who might eventually buy those contracts. If they survived

the voyage to America, they then had to go through a period of

acclimatization, and if they were not brought down by diseases to which they

had never been exposed, then they had at least several years of hard work

before they could again call their lives their own.

Many prisoners were also sent to America by the English courts, generally

as a means of ridding the mother country of the chronically unemployable or

incorrigibly criminal. So many were sent in one period, in fact, that the

governor of Virginia sent a letter of protest to England complaining about

the influx of criminals. Given the conditions of chronic underemployment and

want, the vast majority of crimes at that time were property crimes,

sometimes accompanied by violence, Many imported thieves, however, finding

opportunities available in the New World that did not exist in the old,

managed to go straight and become productive citizens. Others, of course,

continued their violent ways, to the consternation of the colonial

population.

COLONIZATION AND THE ENGLISH NEW WORLD: Points to think about ...

(Copyright © Henry J. Sage 1996-2004)

We will again consider two major sections of colonial America: The South and New England.

Subsistence Economy- the products are made not for sale but for consumption inside of economically closed producing unit (the family, the community); it is opposite the market economy, where the products of work are intended for sale in the market.

Plantation South Brief description of the colonial South from U.S. State Department

Slave labor on an indigo plantation, detail from Henry Mouzon,

Jr. & John Lodge, A map of the Parish of St. Stephen, in Craven County...

(London: 1773)

Source: Special Collections Library, Duke University

New England Brief description of colonial New England from U.S. State Department

Small Size / Medium Size / Large Size

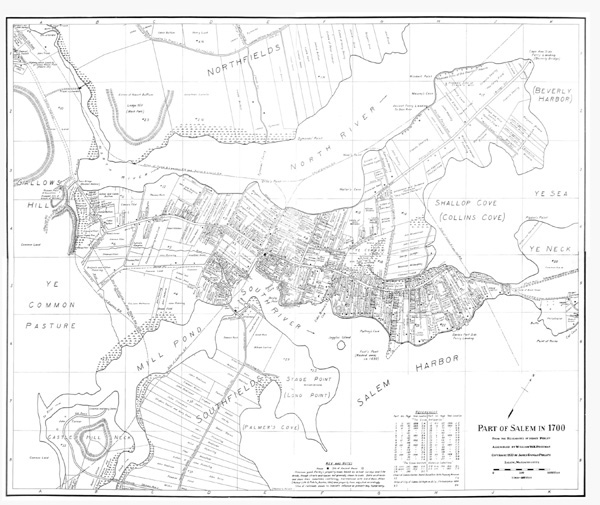

Map of Salem in 1700 by Sydney Perley

a) Shipbuilding became major supplement to fishing and trade

b) Slavery, rum and the triangular trade with West Indies and Africa brought economic wealth to New England

Readings:

- Zinn: 3

- Work with the Colonial section in the Digital History presentation on Mothers and Fathers.

- Tour a colonial family farm site from the Henry Ford Museum

- Short article on Indentured Servitude

Discussion topic: Imagine yourself to be a member of American colonial society. Create a persona for yourself--indentured servant, plantation owner, tradesman, woman on colonial farm, etc. What are the major issues of your daily life?

Project #5: Explore either: Virtual Jamestown or Plymouth Colony Archive Project. Describe how these sites provided you with new insight into colonial America.