1. Mulholland's Dream tells the incredible story of how the hunt for and the exploitation of water brought the city of Los Angeles to life -- and, literally, life to Los Angeles. Evoking the real-life visionaries, scoundrels and dark intrigues behind the fiction of the motion picture Chinatown -- and the remarkable tale of Water Department chief William Mulholland's quest to quench the city's ever growing thirst for more and more water -- the broadcast weaves together past and present to illustrate water's essential role in the history of Los Angeles, as well as the city's challenges for the future.

William Mulholland emigrated from Ireland in 1878, and worked as a ditch digger for the L.A. water system. He quickly taught himself hydraulic engineering, rose quickly through the ranks, and soon became superintendent. He tried desperately to make the exploding population conserve water, but growth sabotaged everything he did, and soon the city sucked dry the little Los Angeles River, its only source of water. Mulholland knew he would have to find new water, and turned to the remote Owens Valley, 230 miles north of L.A.

Between 1911 and 1923, Mulholland's agents quietly purchased 95 percent of water rights to the Owens River. Against overwhelming odds, Mulholland constructed a 233-mile aqueduct across the blistering Mojave Desert to deliver Owens River water to downtown L.A. When the Owens Valley dried up, local ranchers seized aqueduct gates and dynamited the pipeline repeatedly. In 1927, Mulholland declared war, securing L.A.'s legal rights to Owens Valley water with a massive show of armed force.

When the huge San Francisquito dam -- part of the aqueduct project -- burst in 1928, it caused the worst California disaster since the San Francisco earthquake in 1906. Mulholland resigned in disgrace and died a broken man, his real achievement forgotten. But in the 1930s and 40s, L.A.'s City Council, Chamber of Commerce, and its Board of Realtors continued to promote the water search he had set in motion -- this time, 300 miles east to the Colorado River, and, with state help, 600 miles north to the Feather River. But still, it wasn't enough

After L.A. had drained so much water from the streams feeding Mono Lake -- a jewel in the California desert -- the Lake level fell 40 feet. Environmentalists began to take notice. A handful of biologists fought the powerful Department of Water and Power, and in 1988, the state forced the city to stop its diversions of water from Mono Lake. The victory helped open the gates for the conservation measures, progressive water policies, and fragile peace that have come to Los Angeles in recent years.

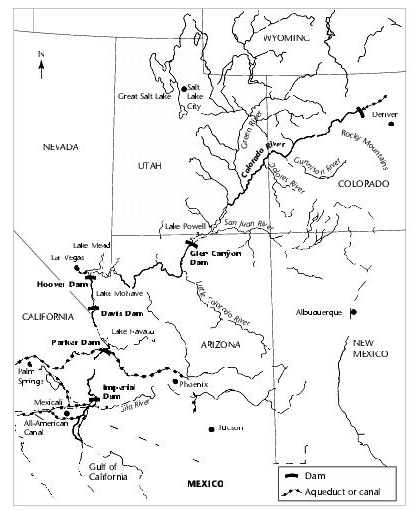

Dams and reservoirs of the Colorado River

An American Nile tells the story of how the Colorado became the most controlled, litigated, domesticated, regulated and over-allocated river in the history of the world. Rich with archival footage and interviews with the river's "shapers" and protectors, the broadcast chronicles how the Colorado became so dammed-up and diverted that by 1969 it no longer reached the sea except in the wettest of years.

On the heels of the Hoover dam came a rush of hydroelectric dams, flood control dams, irrigation dams in California, Arizona, Montana, Washington, Oregon -- all engineering dryness and free-flowing rivers out of existence. Some 55 dams were built on the Columbia River and its tributaries alone -- including the colossal Grand Coulee; by 1956, 90 percent of its salmon were gone and nearly every stretch of the Columbia was a reservoir.

The same year, work began on the Glen Canyon Dam -- designed to generate both hydropower for Phoenix and revenue to pay for still more dams -- that would submerge 186 miles of canyonlands, destroying natural wonderland. Despite the last-minute efforts of the Sierra Club to stop the dam, the reservoir, named Lake Powell, was christened 100 years to the day that Powell had passed through Glen Canyon.

When the Bureau of Reclamation turned next to building two dams in the Grand Canyon, the Sierra Club engaged in a bitter battle -- and finally swayed public opinion -- to block them. But saving Marble Canyon did not stop the flood of people drawn to new homes and new jobs in Arizona, leading to President Lyndon Johnson's authorization of the Central Arizona Project, the most expensive waterworks in Bureau history. Today, with double-digit growth in Phoenix, there's just not enough water to meet insatiable demand. Whereas the Hopi have lived in the desert for a thousand years on tiny amounts of water, Americans built swimming pools and huge irrigation farms in the desert sun -- with water from the Colorado. No river has been asked to do so much -- for so many -- with so little.

With agriculture stretching CVP water to the limit by 1960, California Governor Pat Brown initiated the State Water Project, whose scale nearly equaled that of the CVP. By 1974, the Central Valley was producing 25 percent of America's food -- but much of the profit was captured by giant agri-business companies that bought taxpayer-subsidized irrigation water at extraordinarily cheap rates. As they had for decades, "pork barrel" water projects continued to roll through Congress.

Jimmy Carter was the first president to mount a serious effort to slow the juggernaut of dam building. His investigators uncovered huge cost overruns, environmental threats, and devastating poverty among the farm workers who kept the big farms in business. But caught in a fight for his political life after the failed rescue mission for hostages in Iran, Carter retreated from water reform in the Central Valley. Says Reisner, "He failed to see how water flows uphill toward power and money."

In the mid-80s, the combined effects of bird deformities caused by toxic water run-off from farms, Congressional investigations into water subsidies, and a six-year drought began to turn the tide of public opinion. In 1992, an urban-dominated Congress finally addressed the enormous thirst of California agriculture -- which was, in effect, creating an artificial drought for nature and cities alike -- with a water reform law.

Today, the Central Valley will never again be the same; nearly all the corporate farms have left the valley, along with some smaller farms. The growers that remain must now wrestle with new restrictions on their previously unchallenged water rights and usage.

4. The Last Oasis, offers an eye-opening report on the ways in which water use -- and misuse -- are affecting the daily lives of millions of people in India, China, Mexico, South America, the Mideast, and here at home in Colorado and California. The broadcast explores how, in the face of rising water needs, advances in water conservation may be humanity's "last oasis."Mexico City, struggling to provide water for its growing population, is sinking -- in some sections up to 12 inches a year -- due to overdrawn aquifers. Here, wealthy families get affordable piped water, while poor families must pay high prices for water brought in by truck. In the developing world, 80 percent of illnesses such as cholera, typhoid and dysentery are related to the lack of clean water and sanitation.

In the volatile Mideast, conflicts over the limited waters of the region are only further straining tense relationships. The Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza are angry at the enormous disparity between the amounts of water Israeli settlers receive and the amounts they are permitted; meanwhile, Israel has pioneered drip irrigation and waste-water recycling technologies that are making the Negev Desert bloom.

Back home in Denver, Colorado, the victory by environmental groups in blocking the building of the Two Forks Dam on the South Platte River led not only to the protection of the spring sandhill crane migration in nearby Nebraska, but spurred conservation techniques such as home water meters and "xeriscape," a water-saving landscaping practice. In the Imperial Valley of California, farmers are beginning to cooperate with cities to save water and free up new supplies for urban use; in Los Angeles, a community group has been successful in convincing residents to install new water-efficient toilets, saving the city eight million gallons a day.