Great Plains Thesis _____________________________________________________________________________

Walter Prescott Webb

Great Plains Thesis

_____________________________________________________________________________

Late one night in 1922 Walter Prescott Webb, an embattled history instructor at the University of Texas, sat in his study reading and digesting Emmerson Hough's The Way To The West. Hough's statement that four instruments - the horse, the boat, the ax, and the Kentucky long rifle - had led to the conquest of the American West attracted his attention. As the cold February rain of Austin pelted against the tin roof of his study, Webb puzzled over the selection of the long rifle rather than the Colt revolver upon which Texas frontier plainsmen had depended. He would later write - "Then I saw something very clearly, the great western country, arid and treeless, as distinguished from the East with its rich forest of trees. The horse, yes, he was the mainstay of the pioneer period. I had lived in the horse country. The plainsman was a horseman, and the six-shooter was the natural horseman's weapon. Of course, it was all clear, even the sharp line separating forest and plain." Webb, building upon that moment of insight in cold and rainy Austin, would develop over the next nine years a thesis that provided a framework for studying and understanding the Plains and the Plains experience where none had existed before, solidified his position at the University, and vaulted himself to the upper echelons of his chosen profession.

The Great Plains, published in 1931 by Ginn and Company of Waltham, Massachusetts, remains one of the most important works of American frontier historiography over a half century after it first appeared. It is an examination of the Great Plains and the people who chose to live there between the sixteenth and twentieth centuries. It deals with the Plains Indians, Spanish conquistadors and missionaries, and Anglo-American ranchers and farmers. It is, however, much more than a dry, factual, decade-by-decade history of the region. Rather, it examines the interplay between the Great Plains physical environment and the lifestyles, methodologies, and institutions of the peoples who came to carve out an existence there. Webb very clearly delineated the objective of his study: "The purpose of this book is to show how this area (the Great Plains) with its three dominant characteristics (treeless-ness, levelness, and semi-aridity) effected the various peoples, nations as well as individuals, who came to make and occupy it, and was effected by them..."

He is equally clear about his thesis: "...for this land, with the unity given it by its three dominant characteristics, has from the beginning worked its inexorable effect upon nature's children. The historical truth that becomes apparent in the end is that the Great Plains have bent and molded Anglo-American life, have destroyed traditions, and have influenced institutions in a most singular manner."

The work rests upon two primary ideas. First, Webb maintains that the Great Plains stand as a distinct environmental entity radically different from the wet timbered areas of the East. Three characteristics differentiated the Plains from the East - their level nature, the scarcity of timber, and their semi-arid climate. Webb argues that between the 98th meridian and the western slope of the Rocky Mountain system from Canada to Mexico the two most important elements of life in the eastern United States - abundant rainfall or available water and large stands of timber - were missing. This environment was absolutely foreign to the citizen of the United States, who found the Plains impossible to cope with for a long period of time. Settlement, therefore, jumped from the wet forests of the East to the Western Pacific Slope of California and Oregon. Thus, for a period of time, the United States was a two-ocean land mass with an enormous corridor known as the "Great American Desert" that lay uninhabited and undeveloped by the citizens of the nation.

Secondly, The Great Plains rests on Webb's contention that the Plains environment forced adaptations in American institutions and lifestyles before yielding to settlement and development. Webb argues that Anglo-American civilization had formed in the wet timbered areas of Europe and North America and was well adapted to these environments. But when these people came to this radically different land, their lifestyles and institutions were absolute failures and had to be adapted if they were to survive, much less prosper. In the Great Plains crucible, water transportation, the Kentucky long rifle, forest-based cattle raising, wood or stone fencing and housing, plentiful water, wet land farming, and the laws and literature produced by these elements gave way to the horse, the Colt revolver, the Winchester carbine, the open-range cattle industry, barbed wire, sod housing, windmills, dry land farming, and irrigation as well as new laws and a new literature stressing adventure and suffering. The point is not that these changes occurred but that there was a direct causal relationship between the environment and the change.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The Relationship between The Great Plains Environment and Anglo-American Culture

I. The Location and Environmental Distinctiveness of the Great Plains

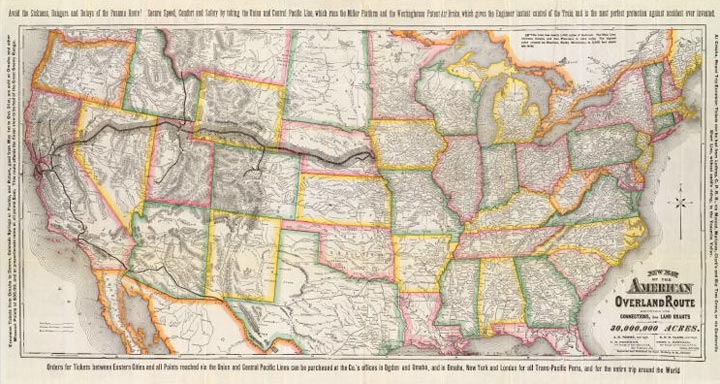

In Webb's thesis, the Great Plains are a vast region stretching from the 98th meridian on the east (a cartographic line running through the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas) to the Pacific slope of the Rocky Mountain system on the west (through Washington state, Oregon, and California) and stretching from Canada on the north to Mexico in the south across the North American continent.

Three physical characteristics differentiate this massive area from the rest of the North American continent:

Webb argues that across this general region two important physical characteristics - water and abundant timber - were missing, making the Great Plains environmentally unique, distinctly different environmentally from the rest of the North American continent.

II. The Institutional Chasm that the Great Plains Represented

Webb maintains that Anglo-American lifestyles and institutions were molded to the physical characteristics of wet, well-timbered environments. Americans had sprung primarily from the wet and timbered regions of Northwest Europe. When they emigrated to North America, they settled along the Atlantic Seaboard which received plentiful rainfall and was densely forested. They successfully settled this region in part because their lifestyles, tools, methodologies, and institutions were suited to this physical environment.

Examples:

Thus, when Anglo-Americans hit the Great Plains in the process of westward expansion across the continent they faced a formidable barrier - an institutional chasm. As Webb states: "For two centuries American pioneers had been working out a technique for the utilization of the humid regions east of the Mississippi River. They had found solutions for their problems and were conquering the frontier at a steadily accelerating rate. Then in the early nineteenth century they crossed the Mississippi and came out on the Great Plains, an environment with which they had had no experience. The result was a complete though temporary breakdown of the machinery and ways of pioneering."

Examples of this inability to cope with the Plains environment using traditional methodologies that had always worked before would include:

Note that because of the failures of their traditional lifestyles, tools, and methods of frontier conquest, settlement jumped across the arid, treeless Plains to the wet, timbered areas of the Pacific Slope - California, Oregon, and Washington state. Thus, because of the environmental uniqueness and strangeness of the Plains to Americans of the United States in the mid-1800s, the nation was transcontinental in name only. There was a vast underdeveloped and forbidding vacuum separating the East from the Far West of the Pacific coast.

III. The Adaptations in Anglo-American Lifestyles and Institutions Forced by Environment

Faced with the total inapplicability of their traditional methods of frontier conquest, these methods had to change if the Plains were ever to be conquered, settled, and fully developed. And indeed they did change - reluctantly and grudgingly - over time.

Examples of Adaptations:

allowing settlers to

convert many areas into productive farming regions.

allowing settlers to

convert many areas into productive farming regions.

Only when these adaptations were made were citizens of the United States able to cope successfully with the physical environment which had originally terrified them as uninhabitable wasteland. The point is not that these changes occurred but that there was a causal relationship between the environment and the change.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The Staged Conquest and Development of the

Great Plains

Another way of thinking about the conquest and utilization of the Far West by the United States is three phases or stages: the conquest and subjugation of the Plains Indians, an era of bonanzas, and permanent development. While somewhat different, this method, on closer examination, dovetails with the model offered by Webb.

I. The Conquest and Subjugation of the Plains Indians

The American military found the Indians of the Great Plains to be a formidable enemy in battle and a barrier to westward expansion that took a quarter century to remove. In part this was because the Army could never bring its full force to bear during part of the era - it was required to occupy the defeated states of the old Confederacy in the aftermath of the Civil War as part of the Reconstruction effort. Even after Reconstruction ended, however, the military faced a formidable foe in dealing with the Indians of the Great Plains. Many were fierce warriors on horseback who struck with lightninglike speed and surprise only to vanish into the vast prairie expanses with which they, unlike the American soldiers, were familiar. Indian resistance to American expansion did not end until the latter 1880s.

While American soldiers played an important role in the subjugation of the Plains Indians, probably the most important role was played by the American buffalo hunter. Buffalo were initially killed for the sheer sport of seeing such an immense animal fall. Then hunters began slaying the animals for their hides alone, leaving the denuded carcasses to rot on the ground. Only at the end of the buffalo bonanza did Americans begin to use and market the meat. By then the buffalo were almost gone.

The buffalo represented the foundation of the Plains Indians culture. This cornerstone was absolutely liquidated in a fifteen to twenty year time span. In 1870 it was estimated that the two great herds of buffalo on the Plains numbered 15 million. By 1890, buffalo hunters armed with Sharps 50 caliber carbines with a killing distance of 600 yards, with the encouragement of the military, had driven the buffalo to the brink of extinction. The Indians of the Great Plains - who used the animal for food, clothing, housing material, tools, medicine, etc. - were just as surely starved onto the reservations as they were driven there by the military at the point of a bayonet.

II. The Era of Bonanzas/Webb's "Primary Windfalls"

Even before the Plains Indians had been subjugated, many Americans attempted to take advantage of the region's resources and many an economic bonanza was there to be found and exploited. Webb deals with these experiences in his thesis in his discussion of the "primary windfalls" that the Plains offered.

Primary windfalls were natural resources or raw materials of the environment that were readily exploitable for the expenditure of very little money....the search for quick riches.

Examples included:

The era of bonanzas was an ordinary albeit profligately wasteful stage of the settlement and development of the Plains. This was a quest to make as much as possible as quick as possible for as little expenditure as possible. It was an era of individuals operating on pennies as opposed to business corporations operating in a structured environment on millions of dollars of investment capital. It was the buffalo hunter with rifle, ammunition, wagon and little else. It was the Texas cowboy who rounded up the wild cattle of South Texas and drove them overland to Kansas. It was the placer miner with a claim and a tin pan to wash the river silt in search of gold. Despite the adventure and romanticism of this period, little of the true lasting value of the Plains was realized during this stage. The true development of the wealth the Plains offered came in the Era of Permanent Development from what Webb referred to as "Secondary Windfalls."

III. The Era of Permanent Development/Webb's "Secondary Windfalls"

Secondary windfalls were natural resources and raw materials that were more efficiently developed and utilized by business corporations. This phase marked a permanent commitment which required the expenditure of vast sums of money. However, it was in the stage of secondary windfalls that the real wealth of the Plains environment was developed.

Examples included:

By the era of secondary windfalls, hundreds of millions of dollars were invested by railroad corporations to provide the Far West of the Plains with fast and reliable transportation. The railroads, seen by Americans as a prerequisite to the full utilization of the Great Plains region as well as to a rapid industrial revolution in the United States, received subsidies from federal, state, and local governments. Sometimes such support came in cash grants or loan guarantees. More often it took the form of grants of land - so many acres from the public domain for every mile of track laid. The railroad used such grants to generate funds by selling Great Plains land to settlers. They would then bring those pioneers to the Plains, transport in the goods and supplies necessary for survival and carry out the resources and products they produced. The railroads connected the Plains with the rest of the country on a cheap, reliable basis. Without the roads, the wealth of the Plains could never have been developed. That is why Americans paid so much to help privately-owned businesses build them.

Summation

In 1850 following the Mexican Cession, the United States claimed to be a transcontinental nation stretching from sea to shining sea. In one sense this was true. Once the Oregon and Mexican Cession territories were added the nation indeed stretched from Atlantic Ocean to Pacific Ocean. But this was only on the map. In reality, there existed a gaping vacuum - the Great Plains - separating the established sections of the country east of the Mississippi River with that of the Pacific coast. Because of their distinctively different and alien environment, the Plains long represented a barrier to American settlement and development. Only after citizens adapted their lifestyles and methodologies to the physical realities of the Plains would the region yield to conquest and utilization. By the end of the 1890s Americans of the United States had grudgingly made those adaptations and began the permanent development of the region's vast potential. Then, and only then, did the "Great American Desert" become a part of the United States and the American experience.

http://www2.austincc.edu/lpatrick/his1302/webb.html

__________________________________________________________________________________