.

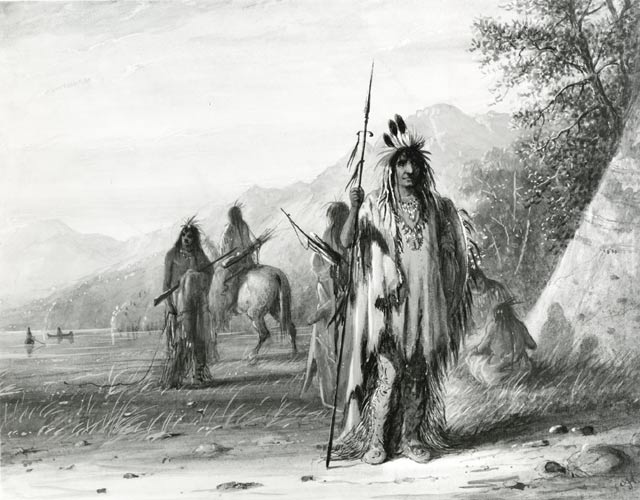

"Shoshone Warrior Smoking his Pipe," Alfred Jacob Miller, 1830s, http://alandp0.tripod.com/popwip/room08/shoshon.htm

Michael Kosuge

Euro-American Influence on Shoshone Men’s Clothing

As Euro-American moved into Shoshone lands, there was a sharing of dress items. Particularly in the "middle ground" of the fur trade, 1820s-1840s, trappers took up Indian clothing items and Indians took up non-Native attire. Later Shoshone, like other Indians, were strongly encouraged by Christian missionaries and by federal agents to take up "American" dress. For example, in the Treaty between the United States of America and the eastern band of Shoshonees and the Bannack tribe of Indians, 1868, Article 9 stated:

In lieu of all sums of money or other annuities provided to be paid to the Indians herein named, under any and all treaties heretofore made with them, the United States agrees to deliver at the agency-house on the reservation herein provided for, on the first day of September of each year, for thirty years, the following articles, to wit:

For each male person over fourteen years of age, a suit of good substantial woollen clothing, consisting of coat, hat, pantaloons, flannel shirt, and a pair of woollen socks; for each female over twelve years of age, a flannel skirt, or the goods necessary to make it, a pair of woollen hose, twelve yards of calico, and twelve yards of cotton domestics.

For the boys and girls under the ages named, such flannel and cotton goods as may be needed to make each a suit as aforesaid, together with a pair of woollen hose for each.

Non-Indian dealers and collectors often refer to an item of Native manufacture as "traditional," generally meaning that the item in question pre-dates Euro-American contact and thus has "pure" ethnographic origins, as opposed to commercial production. This view, of course, negates Indian agency and overlooks the fact that the entire North American continent had myriad intertribal trade networks—and thus some form of commercial production—long before Europeans ever reached Indian country. Following contact with Americans of the Lewis and Clark Voyage of Discovery, Shoshone became active participants in the early fur trade of the Rocky Mountains. Thus, from at least 1825, they had access to manufactured goods and materials and incorporated these products into their daily lives. They also were exposed to Indian people who had not been their traditional trading partners. For example, during his sojourn as a fur trapper in Shoshone country in the 1830s, Osborne Russell reported that he spent one winter in a camp of Shoshones that numbered 20 lodges. About half the lodges were Shoshone families. The others were French and American traders and their wives, who included Seminoles, Iroquois, and Creeks

.

"Shoshone Warrior Smoking his Pipe," Alfred Jacob Miller, 1830s, http://alandp0.tripod.com/popwip/room08/shoshon.htm

"Traditional" Shoshone clothing changed with the seasons, ranging from a simple a breechcloth held on by a belt fastened around the waist for the men and aprons for the women to rabbit fur pants and jackets, and larger animal hides used as capes and coverings. George Catlin’s 1830s depiction of 3 Shoshone warriors, shows them wearing hide robes. The one on the left features parallel lines of quill work. The center hide robe also has lines of quillwork, but also has painted images of horses and riders.

The Shoshone are wearing moccasins made out of animal skin. Animal skins could be molded to the shapes of one's feet, and the deer, elk, or other animal skins were sturdy and long-lasting. Yet, in photographs taken in the late 1800s or early 1900s , Shoshone men are wearing boots, or shoes just like white people.

Next would be the clothing worn on the under part of their

body. Traditionally Shoshone men wore "kilts, " later they wore pants. In the

image below of "A Snake Indian Camp," by Alfred Jacob Miller, 1830s, the

Shoshone man is wearing leggings.

As we take a look of the upper part of the body we can also see that the influence of the non-Natives. Traditionally it appears to be that except on formal occasions not only men, but woman and children as well covered themselves with blankets, under that they wore a simple shirt; most of the time they would add to that a scarf, necklace, or a broach. By the mid-twentieth century Shoshone ranch hands wore the clothing of non-Indian cowboys.

Eddy

Drink (b. 1893 d. 1957) Shoshone, wearing a cloth shirt, vest and pants, leather

cuffs, scarf, reservation hat, and shoes. His clothing typifies that of many Sho-Ban

ranching cowboys at the time. His hair decoration, a beaded strip with ermine,

plus his beaded armbands and tie slide are the only Indian signifiers.

Credit: Idaho Museum of Natural History, Ruffner Collection: 253274

Eddy

Drink (b. 1893 d. 1957) Shoshone, wearing a cloth shirt, vest and pants, leather

cuffs, scarf, reservation hat, and shoes. His clothing typifies that of many Sho-Ban

ranching cowboys at the time. His hair decoration, a beaded strip with ermine,

plus his beaded armbands and tie slide are the only Indian signifiers.

Credit: Idaho Museum of Natural History, Ruffner Collection: 253274

The headwear is another item of clothing that has changed over the course of the western influence on clothing. It appears that Shoshone men decorated their heads with feathers, sometimes only one or two feathers, according to what they were doing at that time. As time went on, Shoshone men started to wear hats just like the Euro-Americans coming into region.

Left

to right: Sonnip or Pohaipe family member, James Edmo, and Jack Edmo (Northern

Shoshone -- at Fort Hall), c. 1901 Men did not usually pose wrapped in blankets.

This might have been the photographer's idea in order to hide non-Indian

clothes. The men have typical reservation-style hats with trimmed feathers.

Credit: National Archives and Records Administration: Still Picture

Branch, Record Group 75-SEI-17

Left

to right: Sonnip or Pohaipe family member, James Edmo, and Jack Edmo (Northern

Shoshone -- at Fort Hall), c. 1901 Men did not usually pose wrapped in blankets.

This might have been the photographer's idea in order to hide non-Indian

clothes. The men have typical reservation-style hats with trimmed feathers.

Credit: National Archives and Records Administration: Still Picture

Branch, Record Group 75-SEI-17

Looking how Shoshone men changed their style of dressing is a good way to see how cultures mix in the western United States By lining up photographs in chronological order it is possible to see how the dress changed as the white people came into the regions where the Shoshone Indians lived. Consider the following images of the Northeastern Shoshone leader Washakie:

This

photograph, c. 1865 and by an unknown photographer, may be the earliest picture

available of Chief Washakie. He is seen with trade blanket, a pipe tomahawk

(either forged iron or brass), an embroidered (possibly beaded) sash, and a

scarf around his neck secured with a metal gorget/bolo (possibly an altered

peace medal). Washakie is often photographed with this kind of neckerchief &

gorget, so these are probably his personal possessions.

This

photograph, c. 1865 and by an unknown photographer, may be the earliest picture

available of Chief Washakie. He is seen with trade blanket, a pipe tomahawk

(either forged iron or brass), an embroidered (possibly beaded) sash, and a

scarf around his neck secured with a metal gorget/bolo (possibly an altered

peace medal). Washakie is often photographed with this kind of neckerchief &

gorget, so these are probably his personal possessions.

Portrait

of a seated Chief Washakie in 1870 by Charles Milton Bell (1848-1893). Bell

accompanied photographer William Henry Jackson and took this shot at South

Pass. Washakie wears a neckerchief with gorget/bolo [possibly a peace medal],

a dress wool outer coat, wool pants, and holds a white hat. His moccasins

appear to be side-seamed and undecorated.

Portrait

of a seated Chief Washakie in 1870 by Charles Milton Bell (1848-1893). Bell

accompanied photographer William Henry Jackson and took this shot at South

Pass. Washakie wears a neckerchief with gorget/bolo [possibly a peace medal],

a dress wool outer coat, wool pants, and holds a white hat. His moccasins

appear to be side-seamed and undecorated.

A

Baker & Johnson photo, c. 1883-1885. Washakie and a girl (most likely a

granddaughter) pose near a teepee. He holds a piece of cloth and points in the

distance. He wears moccasins, a kilt, and a cloth belt. As in the other

photographs of Washakie taken by Baker & Johnson, his shirt appears to be a

plaid or checked calico and his moccasins are plain and undecorated. The girl

wears moccasins, a leather belt decorated with metal, a dress decorated with

teeth, and a bead necklace.

A

Baker & Johnson photo, c. 1883-1885. Washakie and a girl (most likely a

granddaughter) pose near a teepee. He holds a piece of cloth and points in the

distance. He wears moccasins, a kilt, and a cloth belt. As in the other

photographs of Washakie taken by Baker & Johnson, his shirt appears to be a

plaid or checked calico and his moccasins are plain and undecorated. The girl

wears moccasins, a leather belt decorated with metal, a dress decorated with

teeth, and a bead necklace.

An

older Washakie, probably in the early 1890s. Photographer unknown. Note that

his hat has holes in it. He wears pants made from a wool trade blanket,

undecorated side-seam moccasins, and an old top-coat.

An

older Washakie, probably in the early 1890s. Photographer unknown. Note that

his hat has holes in it. He wears pants made from a wool trade blanket,

undecorated side-seam moccasins, and an old top-coat.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

"Chief Washaki," exhibit Wind River Historical Center, 19 September 2003. http://www.windriverhistory.org/exhibits/washakie_2/index.htmBenedicte Wrensted: Idaho Photographer in Focus, Idaho Museum of Natural History, http://www.nmnh.si.edu/anthro/wrensted/intro.htm

Treaty between the United States of America and the eastern band of Shoshonees and the Bannack tribe of Indians, concluded July 3, 1868; ratification advised February 16, 1869. Center for Columbia River History. http://www.ccrh.org/comm/river/treaties/shoban.htm

Stamm, Henry E., IV. "An Introduction to Shoshone-Bannock Art and Beadwork: Continuity and Change in Art and Images in the Northern Rockies," Wind River Historical Center, 2003. http://www.windriverhistory.org/exhibits/ShoshoneArt/history/WHAShoshone.pdf