History 2700 MacKay

Week 3 Mercantilism and Colonial America

We will consider two economic systems in colonial America: 1) Mercantilism, the system invented by Europeans as they invented the modern nation state. This is the economic system which promoted colonization by Europeans and European enslavement of Africans. Some individual merchants will become wealthy in this system--wealth which will in the 1700s become the basis for the new economic system: capitalism, and 2) Subsistence, the oldest economy created by humans; most natives and colonists in the Americas worked in this system.

Early Modern European empires in the16th-18th centuries were all based on a set of economic theories known as Mercantilism. Under mercantilism, colonies existed to enrich the mother country through trade. Extensive trade empires sprang up in this period. Spain dominated in the early period, until their naval supremacy was bested by the English after 1588.

Under mercantilism, governments were expected to heavily regulate trade. It was believed that countries needed a favorable balance of trade to flourish, which meant that they sent out more exports than they took in imports. Mercantilism was a highly competitive system in which nations were only seen as truly wealthy if they were richer than their neighbors. Colonies existed to provide markets and natural resources which the home country lacked. The home country and the colonies were to trade only with each other. National monopoly was the ruling principle.

Mercantilism worked well in the early days, when the colonies were struggling and could only produce raw materials, and depended greatly on their mother countries for finished goods, investment, and military protection from attack. By the 18th century, however, mercantilist principles were far removed from actual practice. Individual European countries couldn't produce enough finished goods or provide enough markets for raw materials for their colonists. The 18th century as a result was the "golden age of smuggling," and mercantile policies were a constant source of friction, as conflicts over it led to wars, including the American Revolution. (See: http://www.loyno.edu/~seduffy/exploration.html)

Mercantilism: From the 15th to the 18th century, when the modern nation-state was being born, mercantilism developed as an economic system based on:

Contrary to popular opinion, New England settlement in Massachusetts Bay was not typical of early America; it was the special case in British colonization. Most early British Americans believed in the established English Church and in the Anglican faith. They were not rebelling against restrictive sacred authority as were the Puritans.

Most colonists came to the New World for

combinations of reasons, and among these, secular, earthly reasons were

prominent. For this reason we begin our search for the essence of American

thinking by entering the mental world, the world of ideas, of the majority of

European settlers during the first century of colonization. The

most typical experiences and ideas, those of the mainstream British citizenry

and their colonies, were found in Virginia and the other Southern Colonies: North Carolina, South Carolina, eventually Georgia.

The initial set of questions is obvious enough: Why did anyone bother

with the New World? What excited British men and women to leave their homes and

lives, to travel for four to six months, at least 3,000 miles, in a boat of less

than 150 feet in length, and to live in a wholly foreign land, without most of

the familiar necessities of life and with an unknown number of beings who were

clearly not interested in English citizenship?

Initial English perceptions from early navigators were that Virginia was

"fat with gold and precious stones," and should be colonized for the greater

glory of England.1

Even before the Virginia Company's ships sailed, an English poet, Michael

Drayton, wrote about Virginia as "Earth's onely paradise." His poem, dedicated

to the imminent launch of the Jamestown voyage, is important for the values it

proclaims; these were widely shared in England at the time.2

Moreover, many of the early settlers could easily be tempted by an earthly

Paradise because their lives in Great Britain were exceptionally lean, and held

no future promise of success.

Historian Daniel Boorstin has termed this strain of thinking boosterism;

it emerged from the English Renaissance. A spirit of promotion was repeated and reinforced as settlement proceeded

from Jamestown to San Francisco during the next 250 years. Before such a

prospect of earthly abundance, danger was dismissed, and complications ignored.

It is also interesting that Drayton hoped not just for political domination and

material wealth in the New World, but also for a new dominion of English

letters.

The first contingent in what was later called the Great

Migration to New England --about 20,000 souls in three decades-- left England in

1630. John Winthrop was the leader, elected Governor of the Massachusetts Bay

Company before a fleet of seventeen ships and a thousand men and women sailed.

Once in the New World, his compatriots confirmed their faith in his leadership

by electing him Governor or Deputy Governor twelve more times. "Scion of an

important gentry family,"

2 and

educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, but not a minister, Winthrop was rather

a wealthy, middle aged, well established London lawyer.

Why would such an aristocratic gentleman convince his family to leave their homeland permanently? Winthrop was not motivated primarily by "modern" self-interest. He was a religious enthusiast who believed that "God will bring some heavy affliction upon this land" [England]. The Puritans he led withdrew from what they perceived as the corruption of the Old World to found an outpost which would eventually serve as a beacon to guide the reformation of England and Anglicanism.

Winthrop did not believe in religious freedom in any

modern sense either. Escape from decay took as its principal aim rededication to

purity of purpose. Impossible in Europe, striving toward perfection was possible

once away from the sources of pollution. Winthrop thought of the Puritan errand

into the wilderness this way:

[5 July 1632] At Watertown there was (in the view of divers witnesses) a great combat between a mouse and a snake; and, after a long fight, the mouse prevailed and killed the snake. The pastor of Boston, Mr. Wilson, a very sincere, holy man, hearing of it gave this interpretation: That the snake was the devil; the mouse was a poor contemptible people, which God had brought hither, which should overcome Satan here, and dispossess him of his kingdom. 3

Winthrop was also decidedly not a democrat. His government became involved

in a long series of "hivings-out:" expelling Roger Williams to restrict his

religious and political freedom of expression (leading to the founding of Rhode

Island); banishing Anne Hutchinson to curb her religious views and right to

express them; forcing the secession of Thomas Hooker's congregation (leading to

the Founding of Connecticut); and refusing to allow the settlement in

Massachusetts Bay of a group led by John Davenport. In Winthrop's view democracy

was an abuse of righteousness; there was "no such government in Israel."

4

The communitarian core of

Winthrop's vision set New England apart from the beginning; but both he and

Captain John Smith in Virginia were typical of the founders of colonies which

combined more than a century and a half later to form the New World republic of

the United States. Each sought to bind the first settlers to a righteous path,

to a community of Christian purpose without dissent, to subjection to authority,

and to the prevailing social structure of few rich and many poor. Christian

Charity was as far from what became one later version of "modern" American

ideas --freedom, democracy, self help, free market economics, and secular

individualism--as can be imagined.

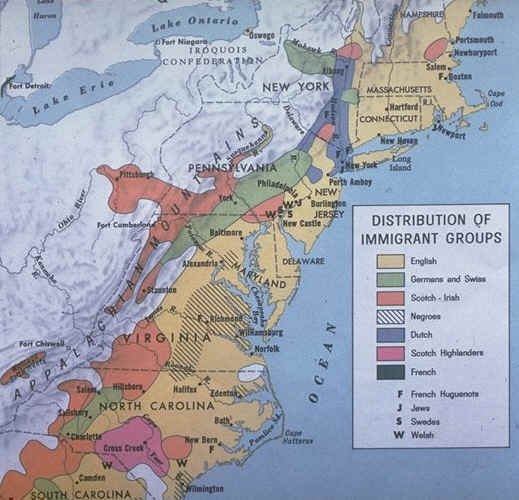

Of the 6.5 million immigrants who survived the crossing of the Atlantic and settled in the Western Hemisphere between 1492 and 1776, only 1 million were Europeans. The remaining 5.5 million were African. An average of 80 percent of these enslaved Africansómen, women, and childrenówere employed, mostly as field-workers. Women as well as children worked in some capacity. Only very young children (under six), the elderly, the sick, and the infirm escaped the day-to-day work routine.

Migration to British North America was more black than white before 1800. About 900,000 Europeans migrated to North America and the Caribbean between 1600 and 1800, while about 2,300,000 Africans arrived in the same period. See: http://www.whc.neu.edu/prototype/12/sumn1.html

Readings: Zinn: 2

Brown: 2 & 3

- use the chart describing the English Colonies.

- short article on Atlantic Slave trade

- Information on the Middle Passage is available from PBS

Recommended Reading: Don't Know Much: 17 - 46

Discussion topics: What was "mercantilism" and why did it encourage European countries to develop overseas empires? What was the "Middle Passage"? How is the enslavement and diaspora of Africans by Europeans a dynamic of mercantilism?

Project 3: Respond to questions 1-3 (p. 41) in Brown and Shannon: 2. There is also information about settlers in Jamestown from Jamestown Rediscovery.

Project 4: Respond to questions 1-3 (p. 61) in Brown and Shannon: 3. Additional images of punishment and posters for runaway slaves is available from the Virginia Humanities.